Whoever expects a ‘pure’ revolution will never live to see it: The UK riots in perspective

|

| Mark Duggan, whose killing by police sparked the riots |

Kevin Ovenden notes that such a reaction is anything but novel:

Predictable reactions from the usual quarters — including David Lammy and the Labour front bench. These were the kinds of reaction from those ideological positions to virtually every riot, from the unemployed protests of the 1930s, through the early 1980s to Tottenham and to South Central LA. Are there some inchoate and reactionary aspects of these events? Sure. Is that their motivation or why they happen? No.

It’s not my intention to respond to such arguments here. Others have done and are doing a better job of that.

Instead I want to argue that the Left should recognise that such resistance — for all the terrible problems and limitations it contains within it — can actually represent something positive. What if we looked at the riots not in terms of a passive balance sheet about their rights and wrongs, but by asking what could be built out of the grievances and energies animating them?

The focus on incidents of small shopkeepers being looted and individual citizens being assaulted that dominates the media is about distracting from the social roots of such a revolt, the state’s failure to immediately impose a coercive solution, and the uprising’s political nature. Yet those three features point inextricably to the uprisings being a mediated expression of more fundamental conflicts and, yes, even the class struggle. Let’s think about the three things in turn.

Society, the state and politics

Firstly, there is the irreducibly social character of the events. It is simply nonsensical to see this in the Thatcherite way, as “there is no such thing as society”, and to presume that the social policies of neoliberal Britain have no relation to the current conjuncture. Perhaps such a claim would be sustainable if the disturbances were strictly contained, or if nothing but looting was going on. But the spread of the uprising and the fact that riot police have been beaten back to the point that many large stores have been cleaned out tells you something about how generalised and socially powerful the riots are.

Despite the focus on deviant individuals — the ones Cameron is threatening to mercilessly track down via CCTV footage — in fact thousands of people have been involved, across age, gender, ethnic (and occasionally class) categories that defy simple boxing of this sort. To see this revolt merely as some twisted continuation of the excesses of individualistic, self-interested, consumer society flies in the face of the large numbers of people coming together on the streets in a way they cannot as atomised commodity purchasers on High Streets and in shopping malls. Whatever the individual motivations and ideas they brought with them, their collective social practice is more than the sum of its parts.

Secondly, the key tipping point in the riots was the inability of the state to immediately restabilise the situation. Put simply, young people in Tottenham completely outmanoeuvred the normally-feared riot police, creating confidence among their peers across the country to do the same. As the Financial Times complained in an editorial on Tuesday, “Over the past four days, the state has lost control of England’s streets,” before advocating a harsh crackdown followed by social policies to address “resentment and dislocation among the have-nots of British society”.

A related article spelled out the seriousness of the crisis for the government:

For Mr Cameron, the early breezy optimism of his premiership has been replaced by a grim mood of crisis management.

Parliament has not been recalled for nine years, but Mr Cameron has found himself being forced to recall politicians for emergency sessions two times in two months — first for the phone-hacking scandal and now the breakdown of law and order in Britain’s biggest cities.

It is not just the government’s authority but that of the state being undermined here. While one is not reducible to the other, it is no coincidence that this political crisis is playing out on the background of the biggest economic crisis since the Great Depression, and one which has spiralled ever closer to the abyss in the last few weeks.

Thirdly, the uprisings are patently political. As Dan Hind has argued in an excellent piece for Al-Jazeera:

[A]ny breakdown of civil order is inescapably political. Quite large numbers of mostly young people have decided that, on balance, they want to take to the streets and attack the forces of law and order, damage property or steal goods. Their motives may differ — they are bound to differ. But their actions can only be understood adequately in political terms. While the recklessness of adrenaline has something to do with what is happening, the willingness to act is something to be explained. We should perhaps ask them what they were thinking before reaching for phrases like “mindless violence”. We might actually learn something.

The fact that so many interviewed rioters have clearly singled out corrupt politicians, bankers’ bonuses, the government’s cuts to social services, and the brutality of British policing as part of their motivation suggests that while such riots aren’t as neat and pretty as a peaceful trade union march, they can still be a pretty clear expression of class anger.

It is worth considering why politics is being channelled in this particular way at this time. But to ask the question is to know the painful answer — the usual mechanisms of expression of class politics have been astoundingly weak and pathetic in their response to the most intense class war from above in Britain for over 70 years. The trade union leadership had to be dragged, kicking and screaming, to call even the relatively mild action to date (a national demonstration in March, a large public sector strike in late June). Much worse, the Labour Party has shifted only fractionally from outright Blairism, which was really only its capture by the Thatcher Fan Club. Ed Miliband has not only attacked the rioters, he also repudiated the public sector strikes, condemned last year’s student protests and doesn’t actually oppose the Tories’ austerity drive, just its speed and depth. Finally, in the poor areas themselves the kind of Black and Asian community leadership that marked the 1980s conflagrations has withered or been incorporated into the Labour Party’s conservatism.

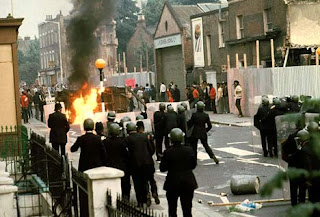

|

| Brixton riots, 1981 |

Potentials and limits

Into such a vacuum has come a political movement much more messy and contradictory, much more contemptuous of the entire edifice of official politics. But in their self-activity, the participants will be making political advances in ways that official accounts cannot comprehend. Chris Harman wrote in a classic article in the aftermath of Britain’s 1981 riots:

For many of those who took part in the riots, it will have been one of the great experiences of their lives. For riots, even more than strikes, provide people who have often lived desolate, atomised, boring lives with an experience of solidarity, of collective power, of being able to affect the course of society at large instead of merely being on the receiving end. That is why after great riots, the participants and onlookers rarely express regret at what has happened, even though the casualties on their side are invariably greater than among the police.

There was, as we have seen, almost no overt politics in most of the big riots. They were spontaneous eruptions, led by those without worked-out political views, drawing behind them a cross section of the youth in their areas. Yet the experience of the riots will have been a very political one.

Furthermore, significant riots almost invariably achieve progressive social reforms. The revolts in the 1980s led to sharp changes in police practices and significant efforts at inner-city regeneration. The Poll Tax riot led to the end of the tax and Thatcher’s loss of authority.

But riots don’t make revolutions. Harman notes that,

Riots, by contrast [with strikes], cannot by their very nature last very long or result in the building of rooted, permanent organisation. They are characterised by clashes with the forces of the state on the streets. Yet a riot cannot hold the forces of the state back from a particular neighbourhood for more than a couple of days at most (unless of course, it develops into something more than a riot, into a revolution that destroys the ability of the state to concentrate its forces in one locality.) Once the police have retaken control of the locality, the crowds that provided people with a feeling of collective power are dispersed. People are driven back into the isolated homes, the segmented experiences, from which the riot drew them. Within days collective exhilaration, the festival of the oppressed, has been replaced by the old atomisation, powerlessness, apathy. The riot always rises like a rocket — and drops like a stick.

Writing as Thatcherism was increasing its grip, Harman could presciently warn that the energy and radicalism of the 1981 riots would founder if not connected to a reinvigoration of workers’ struggles in the workplaces. Today the riots form part of a revival of struggle around the world and in Britain. The complexity of trying to relate the politicisation created on the streets with the wider resistance to the Tories is a discussion all of its own. But to dismiss them for their imperfections and problems would be a grave mistake. As Lenin wrote in 1916:

Whoever expects a “pure” social revolution will never live to see it. Such a person pays lip-service to revolution without understanding what revolution is …

The socialist revolution in Europe cannot be anything other than an outburst of mass struggle on the part of all and sundry oppressed and discontented elements. Inevitably, sections of the petty bourgeoisie and of the backward workers will participate in it — without such participation, mass struggle is impossible, without it no revolution is possible — and just as inevitably will they bring into the movement their prejudices, their reactionary fantasies, their weaknesses and errors.

To imagine otherwise is to try to impose an ideal starting point on the messiness of reality, and to give ground to the moral panic being whipped up not only by the Right, but by too many liberals and Leftists whose concern for the oppressed evaporates when things heat up.