Intended or not, the consequences of riots are not always negative

|

|

|

The riots in the United Kingdom, mainly involving school age and unemployed youth, have provoked a backlash that seeks to paint them narrowly as “mindless”, “criminals”, “thugs” and an “external” threat to social order. Politicians and journalists sing from the same songbook, to condemn and excoriate first and to (preferably not) ask questions later. Voices that raise the social context in which the riots erupted, that point the very political flashpoint of the police killing of Mark Duggan (and its subsequent handling by the police), that argue that rioters’ own professions of being motivated by grievances relating to economic exclusion and racial discrimination — those voices are rapidly cut down by shrill cries that we must understand the rioters less and denounce them more.

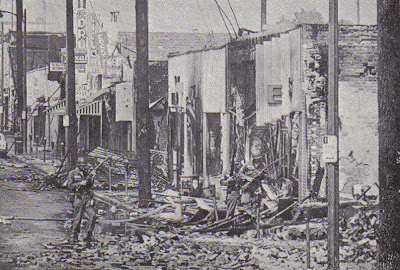

Part of this argument has been an interesting variant on the theme of historical forgetting. In it, the urban uprisings and riots of the past are painted as being of a higher calibre than the current conflagration; more conscious, more political and directed at “genuine” grievances. Their protagonists are painted as being more coherent and directed in their actions; the violence, looting and self-destructiveness reduced to a footnote about collateral damage. The rebellion of yesteryear is romanticised, all the more to point to the sheer self-interest, venality and thuggishness of today’s street fighters.

This argument is necessary in large part because, despite the political class wanting to assure us that their social policies have nothing to do with the social phenomenon of rioting occurring right now, they also need to explain why their predecessors reacted to many past riots with significant reforms.

From riot to reform

The current disturbances occur only months after the 30th anniversary of the Brixton Riots, which produced an outpouring of retrospectives in the British media. While they didn’t shy away from describing the looting and interpersonal violence that is a part of most riots, there was a sense of these having been justified protests against genuine grievances.

The argument has been refined since the current riots started. Katharine Birbalsingh, a conservative blogger for The Telegraph, has opined, “The relationship between the police and the black community in the 1980s was extremely problematic, and I have to say that I have sympathies for the rioters of yesteryear.” But, she claims, times have changed and young Black and Asian children today only imagine that the police are racist. Black author Alex Wheatle, a participant in 1981, says:

Although the circumstances in Brixton 1981 and Tottenham 2011 are remarkably identical; economic crisis, disenfranchised young people, deep cuts in public services and a deterioration in the relationship between young black people and the police, from what I saw in Tottenham I didn’t detect any resolve in the insurrectionists for them to take the police to account. There was no standing their ground making a lasting statement and I couldn’t identify any hint of political motive.

Even Edwina Currie, a Tory MP in the 1980s and 90s, told BBC’s Newsnight that while deep-rooted racism was almost respectable in 1981, it was not now and that the youth on the streets today are simply disconnected with society in general.

Yet the mainstream response was anything but sympathetic at the time. The media and politicians railed against the participants and decried the breakdown of law and order. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher dismissed any relationship between social conditions and the riots, arguing in terms similar to today’s politicians, “Nothing, but nothing, justifies what happened.” She opposed increased investment in the inner cities, claiming, “Money cannot buy either trust or racial harmony.” And when the left-wing Labour local mayor attacked the brutal and racist policing methods of the time, focused on constant stop-and-search of Black men, she railed, “What absolute nonsense and what an appalling remark … No one should condone violence. No one should condone the events … They were criminal, criminal.”

Despite this, riots spread across the country in the summer, the biggest being in Toxteth, Liverpool. Again like today, many of these were referred to as “copycat”, in order to try to depoliticise their meaning. Eventually they dissipated or were repressed by major policing operations. But then Thatcher’s Home Secretary called an inquiry, chaired by Lord Scarman, which confirmed the exact opposite of what the government had been saying. For Scarman the riots represented a spontaneous outburst of built-up resentments, triggered by specific incidents. He highlighted racial discrimination and neglect of inner-city social conditions. He called for “urgent action” to prevent racial disadvantage becoming an “endemic, ineradicable disease threatening the very survival of our society.”

In an era of rising conservative politics, governments were slow to address Scarman’s recommendations. Rioting against police intimidation broke out again in Brixton in 1985. But Scarman laid the basis for decades of patient, detailed work by British police to shift their culture. More Black and Asian officers were recruited, community partnerships were developed and stop-and-search powers curtailed. Furthermore, governments paid more attention to inner city areas, and the rise of a Black and Asian middle class allowed the incorporation of community leaders into official power structures. Some inner city areas, like Brixton, have seen rapid gentrification and urban renewal as a result of long-run government policies.

Riots in the UK have not been the only ones to end in significant government reforms after the dust of “re-establishing order” settled. The Black urban revolts of the 1960s in the United States had many of the characteristics of today’s riots, yet tend to be seen as part of a wider arc of a positive struggle for Civil Rights. In the 1960s they led to President Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” and “War on Poverty” initiatives, major reforms of civil rights legislation and extensive social programs. Yet if rose-tinted glasses are removed they had all the problematic elements that commentators decry today: Lack of political coherence, apparently random attacks on shopkeepers and individuals, the mass involvement of marginal people whose livelihoods came from petty crime and drugs. And the same sense of chaotic, apolitical liberation from police rule that so outrages middle-class commentators was also present, as this account of the Watts Riot argues:

“For the rioters, the riots were fun … There was a carnival in the middle of the carnage. Rioters laughed, danced, clapped their hands, many got drunk. Children stayed out all night … contrary to the usual pattern of riots, where was hardly any sexual delinquency …”

Similarly, the Los Angeles Riots of 1992, with their denunciation by George Bush Sr. as “purely criminal”, “mob brutality” and “not about civil rights”, led to significant changes in LAPD practices, compensation for Rodney King, and government spending designed to partially ameliorate the social conditions in which they arose.

And of course Britain’s own Poll Tax Riot of 1990 not only sunk the hated tax; it was instrumental in the Tory Party’s decision to dump Thatcher not long after.

These are riots, not revolutions

Of course there are strict limits on these developments, which go to the heart of this week’s explosion. Police deaths in custody between 1998 and 2010 numbered 333, with not a single officer convicted over one. And no police officer has ever been convicted over the death of a Black man in custody. Examples of “community policing” targeting gun crime in the Black community, like Operation Trident whose officers killed Mark Duggan, may be seen by officials as helping local people but can also be experienced by locals as a new form of racial profiling and harassment. Addressing ethnicity in the abstract doesn’t remove the class issues surrounding street crime and the police response.

Things have changed socially, too. The New Labour years saw a massive increase in wealth disparities in London in particular, as a new financial class rose alongside continued stagnation of local economies. Tony Blair and Gordon Brown sought to overcome the UK’s relative economic decline by turning it into a financial powerhouse, centred on the City of London. This has driven a pattern of gentrification where a wealthy middle and upper class now live alongside some of the poorest, breaking down some of the segregation of the past. This helps explain disdain of some rioters against “their” communities and “their” local businesspeople (although by far the majority of looting attacks seem to have been on major corporate chains). With youth employment at record lows and austerity measures clearly designed to protect the Tories predominantly middle-class voter base from real pain, the sight of local wealth alongside squalor was likely to be a significant contextual factor in the current rioting.

And on the flipside, in areas like Clapham and Ealing — where much has been made of the (worryingly reactionary) middle-class #riotcleanup movement — and Dalston — where business owners have organised significant self-defence — the sense of “us against them” seems to run both ways locally.

The key to understanding the effectiveness and limitations of riots by the oppressed is in their essential feature: Their ability to break down normal processes of state coercion at a local level, which opens the space for all kinds of behaviour that is normally criminalised and controlled by repression (or at least its threat). This is why a Financial Times editorial earlier this week fulminated, “Over the past four days, the state has lost control of England’s streets,” before advocating a harsh crackdown. But, in recognition of past patterns, once the state was back in charge this would have to be followed by social policies to address “resentment and dislocation among the have-nots of British society”.

Yet the relative lack of coherent organisation and political direction embodied in riots means that they cannot threaten state power more widely than in particular localities or for relatively brief periods of time. They are not, simply put, revolutions. While the current UK riots can be seen as part of a wave of popular resistance to economic crisis and austerity currently sweeping the globe, they are not the same thing as what happened in Egypt from 25 January, when mass, organised protests erupted and drew in unprecedented numbers of people. Decried by Mubarak as criminality in much the same way as David Cameron does today (right down to the calls for limiting social media!), those protests also overwhelmed riot police, but across pretty much every significant urban centre in the country.

Writing after the 1981 riots, the late British political writer Chris Harman argued,

Riots, by contrast [with organised political protests and strikes], cannot by their very nature last very long or result in the building of rooted, permanent organisation. They are characterised by clashes with the forces of the state on the streets. Yet a riot cannot hold the forces of the state back from a particular neighbourhood for more than a couple of days at most … Once the police have retaken control of the locality, the crowds that provided people with a feeling of collective power are dispersed. People are driven back into the isolated homes, the segmented experiences, from which the riot drew them. Within days collective exhilaration, the festival of the oppressed, has been replaced by the old atomisation, powerlessness, apathy. The riot always rises like a rocket — and drops like a stick.

This is not a reason for those concerned with the plight of the poor, marginalised and oppressed to join the carnival of reaction being led by the political and media establishments. Such posturing and the summary sentences being handed out are part of a moral panic designed to make people feel scared and powerless, to crush the notion that authority can be defied. The thrill of the riot has to be replaced by a similarly intense emotion of fear, and so the more sadistic the threats by the government the easier its job in regaining control.* They are also designed to divide communities further, between the minority “other” (the rioters) and the “respectable” people who stayed at home. Of course, the incidents of quite respectable people joining the riots are a sign of how difficult those divisions are to draw in reality. And the race card is being played by contrasting nice, middle-class Asian or Turkish shopkeepers against feckless criminal African-Caribbean youth, despite the very mixed ethnicities of the participants.

But, as I have written elsewhere, the riots’ relative incoherence (and even the greater prominence of looting as what Kings College Professor Alex Callinicos has called “do it yourself consumerism”) must be laid squarely at the feet of the political class, in particular the Labour Party and the trade union leadership. After capitulating to the depoliticising mantra of neoliberal policy-making and the promulgation of consumerism-as-liberation over the last two decades, they have now failed to mount a serious challenge to the harsh austerity policies of the Cameron-Clegg coalition. Ed Miliband, in particular, has not just condemned the riots but also student protests and public sector strikes. He agrees on the need for austerity, just differs on how fast and deep it should proceed. With such a vacuum of political leadership, it is no wonder that the social pressure cooker’s lid can blow off in the form of riots that are political but not a politically conscious movement.

Things may go one of two ways in the wake of the riots. Either the political establishment will — as its forbears did — grudgingly accept its responsibility for allowing the conditions that underpinned the riots to fester and grow, and implement reforms to address them. Or, as seems more likely in a period of deep global economic crisis, they will opt to continue their current austerity drive to satisfy the demands of big business and the rich. If it is to be the second option, then we can expect more riots and the possibility of even wider and more radical expressions of discontent. Then the spirit of Tahrir may well yet come to Trafalgar Square.

* Thanks to Anindya Bhattacharyya for this insight on the psychology of the crackdown.