New revolutionary rehearsals. Part two: From democratic to social revolution

|

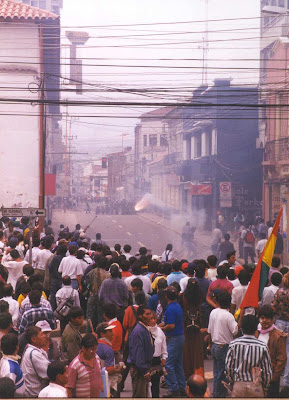

| Bolivia’s water wars |

SPECIAL GUEST POST BY COLIN BARKER

In the last post we published the first half of Colin Barker’s new introduction to the South Korean edition of Revolutionary Rehearsals, looking at the trend towards ‘velvet revolutions’ or ‘negotiated transitions’ in the neoliberal era. In the second half he looks at how the contradictions of the neoliberal era have not only spawned new resistance but opened up the possibility of fundamental social transformation.

The past 24 years have thus provided many more materials on ‘revolutionary rehearsals’. And the coming years will surely provide many more. The world is still reeling from the largest global crisis since the Second World War, whose after-shocks are being felt in both the heartlands and the peripheries of world imperialism. Everywhere, national and trans-national governmental institutions are demanding that working people must pay for the banking crisis with cuts in real wages, welfare services and pensions — while those responsible for the crisis are walking away with larger salaries and bonuses. Transnational bodies like the IMF, the World Bank and the WTO, which lock national governments into their neo-liberal policy embrace, do not even pretend to be responsive to popular movements and demands.

There is thus every reason to suppose that mass popular movements will again — and in much less than the next quarter-century! — pose directly the possibility of a socialist transformation of society. Possibility is not, however, inevitability. Reflection on previous experience suggests some of the conditions of success.

What marks the beginnings of a revolutionary era is the entry of large masses of the oppressed and exploited into active engagement with political life. The opening of mass struggles ‘from below’ signals the breakdown of political ‘normality’, a condition nicely described by American historian, Lawrence Goodwyn as one where ‘A relatively small number of citizens possessing high sanction move about in an authoritative manner and a much larger number of people without such sanction move about more softly.’ [1] Normality is commonly preserved by a mixture of fear and disbelief in the possibility of significant change. Its breakdown is marked by a release of popular energy and imagination.

The question is then, what form does this take? How are popular aspirations formulated and expressed? Is the old distinction between ‘political’ and ‘economic’ demands maintained, or do they begin to dissolve — as famously analyzed in Rosa Luxemburg’s account of mass strikes? [2] Capitalism’s supporters always hope to maintain this separation: recently the Financial Times, the leading British capitalist newspaper, summarized its concerns about the ongoing revolutionary situation in Egypt by saying, ‘The economy itself must be depoliticized’. [3] That ‘depoliticization’ of economic life was what the capitalist class loved about the 1989 revolutions in Eastern Europe. Socialists take the opposing view, asking whether popular practical hopes are invested only in a change of government, or also encompass demands to do with, for example, wages and prices, working conditions, democracy in trade unions, and managerial power in workplaces. Is economic as well as political corruption challenged from below? Are there processes of ‘saneamento’ (the Portuguese term from 1974), of ‘cleaning out’ those whose power depended on their connections with the old regime? The expansion of struggles focused on ‘economic’ questions is a vital part of every popular upsurge with the potential to change the very bases of social life.

What’s involved is not just a matter of weakening and undermining old patterns, but of beginning to create and spread new kinds of relationships and institutions, in all areas of social life. What kind of new regime is possible? If no new regime is more democratic than the movement that creates it, we need to ask whether those engaged in revolutionary upsurge are building new kinds of democratic organizations, not just in the obviously ‘political’ sphere but in neighbourhoods and workplaces, in the organization of ‘public order’ and justice, and in the institutions of the popular movement themselves, in unions and parties, in people’s assemblies and workers’ and peasants’ councils. Is the general demand for democracy and mass participation in every sphere of social life emerging, and being theorized and broadcast across the insurgent movement?

A mass movement from below can generate the conditions for this to occur, as nothing else can. For in such a movement, popular learning and development speed up enormously, once the old barriers of fatalism and fear begin to dissolve and those who ‘moved about more softly’ start to feel their accumulating strength — and to mock and pull down the formerly powerful. The idea that the whole of society can indeed be remade on new foundations takes on a suddenly realistic hue. Issues that once were the debating topics of tiny minorities can become practical questions for millions: what kind of economy do we actually want, are working people capable of running society themselves?

It is in relation to just such matters that we can measure the deepening of popular revolutions. A merely ‘political’ revolution that overthrows an old government can be accomplished by a determined minority. One estimate is that around twenty per cent of the population of Egypt was actively involved in the overthrow of Mubarak — a brilliant popular achievement, but still by a minority. A socialist revolutionary process, however, will necessarily involve a far larger proportion, for it must reach far deeper into all the forms and aspects of everyday life. To the degree that working people do begin to manage their own productive and organized life activities under their own steam, developing democratic means of decision-making, to that degree also their confidence in their own cooperative powers can develop. Their own individual and social transformative growth becomes both a means and an end. The importance of such ‘cultural’ and ‘psychological’ development can hardly be over-estimated.

Successive approximations

Revolutionary movements make it possible to set aside old assumptions and prejudices, whether about religious, ethnic and national antagonisms, or gender superiority and difference. However, there is nothing automatic about such advances: they have to be fought for openly, and the proponents of old divisive ways pushed back in favour of new, enlarged ideas of solidarity. Popular movements do not only contest power with the old rulers, they involve deep and contentious debate about their own forms, their own procedures, their own meaning and purpose. They develop, for good or for ill, through processes of mass learning, by debating, testing and absorbing the lessons of different engagements with the old forces and forms of authority, through defeats and advances, dramatic turning points and reversals. Leon Trotsky described this experimental method of discovery and learning as one involving ‘successive approximations’ by mass movements, a method involving great leaps of understanding and imagination as well as collapses of mutual trust and fierce internal arguments.

To the extent that, in their development of new forms of organization, and their challenges to old forms of authority, movements burrow away at the institutional and cultural supports of capitalist power, a revolutionary period is marked by a peculiar form of contested government, sometimes termed ‘dual power’ or ‘multiple sovereignty’. The former ruling classes, and their very principles of power, are severely weakened, but they have not yet been decisively replaced. The rising power of the movement of working people has not yet gained full power and confidence in itself. It is a situation of huge instability, but also one, in Trotsky’s phrase, of great political ‘flabbiness’. The question of the moment becomes ever more stark: will the popular mass movement march forward to take power for itself, through its own new democratic institutions, or will sections of the old ruling class exploit its uncertainties, divert its energies, and find ways to demobilize the movement and recover its old power in some new form?

In this volume’s chapters on Chile and Poland, that ruling class recovery took form as military dictatorship, a particularly brutal form of capitalist rule. Barely less brutal was the Islamist dictatorship in Iran, erected on the defeat of left and secularist forces in the 1979 revolution. But the chapter on Portugal shows that ruling classes have other possibilities, not least a recourse to the politics of social democracy. In place of the direct contest of mass movements with capital and the state, let’s have an election! In just this way, the five years of revolutionary contestation in Bolivia from the great victory of the Cochabamba ‘water wars’ of 2000 ended with the election of the left government of Evo Morales in 2005. Popular energies were displaced onto the electoral path. In one sense, the Morales election registered a huge victory for the people of Bolivia — but also a failure to resolve the crisis of Bolivian society. The capitalist class’s property and power remained intact, poverty for the mass of Bolivians continued. [4]

In conditions of ‘dual power’, the role of revolutionary Marxist parties takes on its maximum significance. Such conditions produce opportunities, not only for socialist advance, but also for reformist politicians to seek to ride to office on the wave of popular discontent and mobilization. For their project to succeed, it is vital that the popular movement de-mobilize its forces and lower its aspirations, to focus instead on the parliamentary arena. In such circumstances, revolutionary socialists’ active involvement in the movement becomes vital, for they can develop an alternative pole of argument and agitation, stressing the need to maintain and further develop the movement’s independent activity and organizations — for it is in these, and not in parliament, that the possibility of a real social transformation resides.

In a world locked in crisis, where the flames of revolt are once more rising, these matters will again be posed as practical questions. The re-publication of this volume seems timely.

The English language version of Revolutionary Rehearsals is currently in print via Haymarket Books here. The South Korean version is at the publisher’s website here. The original was published by Bookmarks in the UK. A website of Colin’s writing can be found here.

[1] Lawrence Goodwyn, Breaking the Barrier. The Rise of Solidarity in Poland, New York: Oxford University Press, 1991, p xxi

[2] Rosa Luxemburg, The Mass Strike, The Political Party and the Trade Union, London: Bookmarks, 1986

[3] ‘The economics of the Arab spring’, Financial Times, 24 April 2011

[4] Jeffery Webber has chronicled the Bolivian experience in a three-part article in Historical Materialism (vol 16.2-4, 2008) and in his book From Rebellion to Reform in Bolivia: Class Struggle, Indigenous Liberation, and the Politics of Evo Morales (Chicago: Haymarket, 2011)