Gratuitous advice: Inviting the Greens into the mainstream

I wonder how you see the Greens party. I mean is it an ecological party or is it maybe Australia’s only left wing party?

—Laurie Oakes to Bob Brown, 11 July 2010

The persistence of polling showing the Greens at 11-13 percent has meant that for the first time in a federal election the party has been taken seriously by the MSM. Apart from some unsavoury red-baiting directed at Lee Rhiannon, the usual scare stories about crystal meth being available to kids on street corners have been few and far between. Instead we have seen significant media time, positive coverage of the party’s most important lower house campaign, reports on relatively minor preselections, and detailed discussions of party policies, especially those on economics.

At one level this represents the confluence of increased electoral weight and a media desperate for a story outside the dispiriting campaign being run by the major parties. Even the most insular press gallery journalist probably has some unconscious awareness that the mass of the population has switched off, and the enthusiasm around the Greens sticks out like a sore thumb. Now that the party is polling so strongly its ideas are given more credence.

But there is a second process going on here, which is that of co-option. It is one thing for a party like the Greens to be derided for its fringe views when it can wield little power to affect outcomes inside the parliamentary arena, another when it may have a seat at the negotiating table around crucial legislation. Better sometimes to tame or neuter a threatening force through kindness than stiffen its resolve through abuse.

Co-option in the current phase has taken the form of gratuitous advice, from both friend and foe, to convince the party that it really can be a serious player if only it moderates its policies and approach. This has come alongside statements from both prime ministerial aspirants that they could work with the Greens if the party’s potential balance of power role in the Senate came into play.

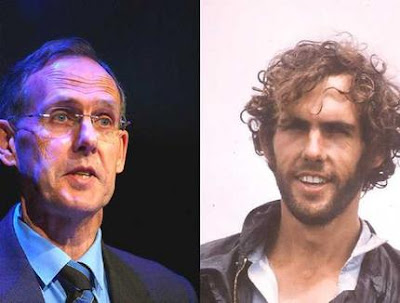

The most developed form of advice has, however, come from a Greens member best known for his powerful exposure of the big business carbon lobby, Guy Pearse. Writing in last month’s The Monthly (paywalled, see my reply here), Pearse eulogises the party but then launches a pointed attack on its Left wing, arguing that “perhaps the biggest obstacle facing the Greens is internal”. Instead, the Greens should build a “broad church” of support that goes “beyond Right and Left”, enticing growing numbers of refugees from both sides of politics.

Despite 19 years as a member of the Liberal Party, Pearse is no conservative, having had a light-bulb moment when confronted by the dark forces stifling action on climate. He rightly excoriates the major parties for falling into the thrall of “market fundamentalism” and sees the Greens as capable of filling the vacuum created by their march to the Right. In a line recently milked by Bob Brown, he says “the Greens now look more liberal than the Liberals, more labour than Labor and — unsurprisingly — far greener than both.” He also draws an inexorable arc of increasing Greens influence, starting in the Tasmanian wilderness and built around Brown’s inspiring record of activism and sacrifice.

I get the feeling there’s more than a little projection in Pearse’s approach, if not the fervour of the recently converted. There has been a tendency for sympathetic accounts of the Greens to have a quasi-spiritual edge, painting Brown in almost messianic terms. Pearse’s claims also contribute to a mythologising of the party’s successes. For example, as I have written elsewhere, outside of Tasmania consistent electoral success did not come until the late 1990s. It was then that party found a new role as a national electoral expression of new anti-systemic movements opposed to corporate power, mistreatment of asylum seekers and the War on Terror. It did so by consciously positioning itself to the Left of the ALP on these issues.

It is ironic that Pearse is so hostile to the party’s Left because a left-wing appeal has been crucial to the Greens’ electoral success. He lays in to preference deals with the ALP (something Brown has also done, after he and the party machine fell out over preference strategy last year), instead arguing that deal-making of all sorts should be contemplated with both major parties. Finally, his prescription for how the Greens can overcome the calamitous and irreparable state of official politics is through … entering, as junior partners, into coalition with the politically bankrupt majors!

This is not some facile debate about principle versus compromise, as it is often painted in the mainstream (and to an extent by Pearse himself). Rather, it is a question of whether the Greens’ aspiration to be a transformational force can go beyond accepting a few progressive crumbs as reward for rehabilitating a broken mainstream. Is there something truly new about the Greens that will allow them to break with the established pattern of radical parties repudiating the characteristics that won them success in the first place?

At last weekend’s national campaign launch, Christine Milne spoke passionately of “new [Greens] ethic for the 21st Century”, echoing the vision spelled out in the party’s 1996 manifesto, co-authored by Brown and philosopher Peter Singer. But in the absence of a serious analysis of social structures and power relations, the resort to an ethics-based political philosophy implicitly leaves the fate of one’s project in the hands of committed and well-meaning leaders, role models for the new society.

It seems a daring leap of faith to presume that growing engagement with the parliamentary system and the state machine will leave that ethics unchallenged and unaltered.

In an upcoming post I will look at the Greens’ economic policies, and whether they are really as transformational as the party’s rhetoric would suggest.

Tad,You are right to question the ability of The Greens to be both a mainstream and radical force. The point Lee made recently at the left renewal conference that keeping The Greens left is the major challenge the party faces must be acknowledged. Although I have argued that there is room for debate about what this really means. The Greens are on the left but not of the Left. I believe it is this cultural issue (a question of political tribalism and identity rather than ideology) which is at the heart of apparent divisions within The Greens.Karla Sperling