The Pope, the Vatican and the limits of liberal critique

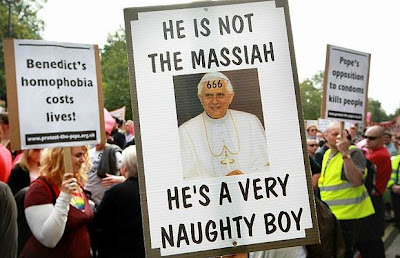

If the protests against the Pope during his recent visit to the UK prove anything it is that the Vatican has really upset people. But beyond that, the motivations behind the protests are a complex mix of righteous anger, progressive criticism and reactionary sentiment, with the boundaries between them difficult to tease out.

What is one to say of anti-Papal protests in a country renowned for systematic sectarian oppression of Catholics in at least two of its territorial components, Northern Ireland and Scotland? How is one to take the involvement of figures like Richard Dawkins, whose contempt for believers is visceral and who has called the Pope “the head of the world’s second most evil religion”? And what is the logic of an outbreak of Pope-bashing in a Europe where polite liberal opinion has demanded “secularism” as a thinly veiled ideological cover for Islamophobia?

That aside, there is much to recommend in Geoffrey Robertson’s trenchant critique of the Vatican’s scandalous attitude to child sexual abuse by its clergy, The Case of the Pope. It forensically details how Church hierarchies systematically covered up a staggering number of cases through the use of internal “investigations” and Canon Law, the latter an in-house system of rules and (pathetically mild) sanctions, in preference to legal reporting to authorities in nation states where the crimes were committed. Ratzinger, head of the central body administering this quasi-legal apparatus from 1981 to 2005 when he became Pope, repeatedly issued directives and massaged guidelines to avoid public exposure of paedophile priests and in the process facilitated their further criminal activity.

Robertson, unlike many critics of the Catholic Church, is sympathetic to its flock and reserves the full force of his attack for its upper echelons. But he over-eggs his case in three ways that leave his account with less explanatory power than it could have had.

Firstly, he raises child sexual abuse by clergy to a level of unique moral importance: “The sexual abuse of children is an outrage — bad enough in ordinary cases of ‘stranger danger’ paedophilia, and worse when teachers or scout-masters or baby sitters or parents abuse the trust placed in them […] But worst of all are priest offenders.” He musters some psychological arguments to suggest that Church abuse victims suffer more than others, but this seems to be based on the spurious notion that Catholics are more “indoctrinated” to trust priests than other abuse victims are to trust their abusers. How one’s own parent sexually abusing them is less damaging seems to me more a debating point than a rational assessment of the horrors (let alone causes) of sexual abuse.

Secondly, he spends much time undermining the Vatican’s claim to be a nation state and therefore its right to use Canon Law under a kind of diplomatic immunity. He delineates many good reasons why the Vatican doesn’t conform to the usual definitions set down by bodies like the UN. But Robertson is unable to provide a convincing answer as to why other states allow the Vatican to continue operating in this way. China Mieville has cogently argued that international law is not administered by supranational bodies that have real power over things like state creation. Rather, precedent is set by the balance of forces between the most powerful states and rewritten to reflect the way their actions reshape the globe, whether through war or its threat. Robertson cannot grasp the positive role the Vatican plays in cementing conservative ideologies that benefit elite interests within apparently liberal and secular societies like our own.

It becomes apparent that this lacuna arises from Robertson’s political preference for a certain type of liberal imperial order, one that is let down by the West’s insistence on propping up the Vatican’s legitimacy. Therefore he pours scorn on the Church’s condemnation of several US- and NATO-led military actions as part of his case that the Pope should stay out of world affairs. Surely the ability of the Pope to relate to justified anti-war sentiment goes in some part to explaining the Church’s continued adaptability in the modern era. And while he touches on the systematic campaign against left-wing currents within the church that was the previous Pope’s guiding mission, Robertson misses how well this tied into the general lurch to the Right that was driven by Western elites globally. On his account the internal machinations of the Church remain abstracted from the real world, all the better to shower the Vatican with opprobrium while portraying Western rulers as mere dupes of Papal nastiness.

Thirdly, Robertson argues that if the Vatican wants to be considered a state then its supreme leader might be prosecuted for “crimes against humanity”. Here he effects a sleight-of-hand in trying to paint the cover-up of the actions of abusive priests as akin to the cover-up of state-inspired atrocities, whether in times of peace or war. Yet unless he is willing to accuse the Vatican of systematically wanting to abuse children, the crimes committed by priests represent a far more banal evil, and their cover-up a more prosaic attempt to hide an internal scandal at a time when the Church’s authority has already been dramatically eroded.

On why there is such a high rate of paedophilia among priests Robertson gets his criticism backwards. It is not, as he suggests, that chastity is necessarily a harbinger of abusive behaviour, but that an archaic and closed institution obsessed with PR damage control has provided a safe haven for some of the most disturbed products of our society to ply their damage.

Blinded by his selective moral outrage, Robertson makes half a case against the Pope. Understanding the Church’s ability to speak to people’s hopes for a better world as well as its reactionary prescriptions and internal corruption would provide a clearer focus as to how to undermine its malign influence.

I suspect this paragraph points to the real explanation for this well-connected and hugely-hyped international campaign to de-legitimize the Catholic Church (Geoffrey Robertson is only one player in a large orchestra):"he (Geoffrey Robertson) pours scorn on the Church’s condemnation of several US- and NATO-led military actions as part of his case that the Pope should stay out of world affairs. Surely the ability of the Pope to relate to justified anti-war sentiment goes in some part to explaining the Church’s continued adaptability in the modern era."By increasingly associating the Catholic Church, in the minds of the secular majority of westerners, with kiddy fiddling, the moral legitimacy of the Church is weakened and its capacity to oppose war-mongering neocon polices correspondingly diminished.