Fractured voice, fractured nation?

By Tad Tietze

This post is dedicated to the memory of the essayist and blogger The Piping Shrike, who passed away suddenly and unexpectedly on 15 July this year. A dear friend and a key inspiration for this blog’s “anti-politics” analysis, as well as my thinking on race and the Constitution.

Strip away the rancour that has characterised debate leading up to this weekend’s referendum on a Voice to Parliament and a near-certain majority No vote will go down as the latest in a long line of failures to resolve the contradictions faced by the Australian state in addressing the “Indigenous problem” that bedevils its legitimacy.

That legitimacy is one which has been undermined by having its origins in the colonial dispossession of the continent’s original inhabitants, and which — to date — has been managed in explicitly racial terms.

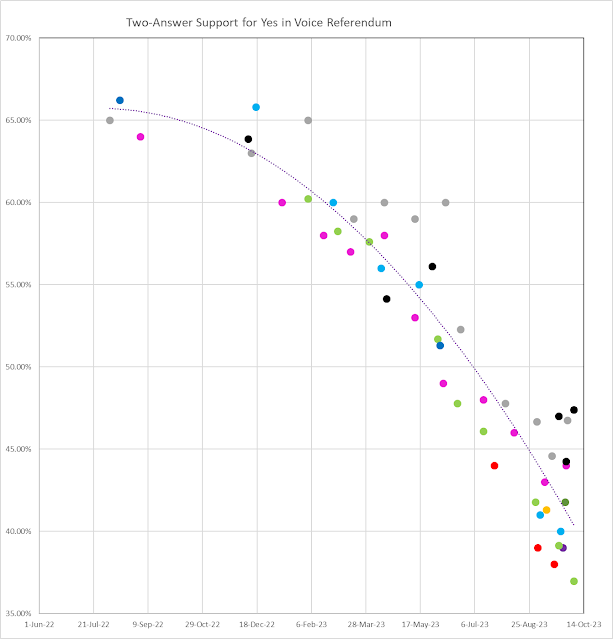

Credible opinion polls have converged on the harsh reality that the campaign to entrench an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander advisory body in the nation’s Constitution is destined to fail, most likely by a wide margin. So stark are the trends that, as of this writing just days before the vote, only some combination of the biggest polling failure and the biggest late swing in Australian electoral history could deliver a victory for the Yes campaign.

A TORTURED PROPOSAL

The proposed constitutional amendment demands the formation of a new “body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice” to “make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples”.

Paradoxically, the “solution” embodied by the Voice leaves intact the racially discriminatory aspects of the Constitution, especially the “race power” of Section 51(xxvi), which was originally included to allow discrimination against “coloured races”, especially Asians, and which underpinned the nation’s infamous White Australia Policy.

Leading Voice supporter and constitutional law expert George Williams has argued that the Voice is seen by Indigenous leaders as a way of advising on the use of the race power to “move away from negative, race-based interventions to laws that drive better outcomes for our First Peoples”.[1] It’s probably for this reason that the Voice will have not only its own Section but its own Chapter in the Constitution; to give it sufficient weight to impact on racially discriminatory powers that have in the past been used against (as well as for) Aboriginal people.

Notably, however, the proposed amendment includes nothing about the Voice having to be representative or act in the interests of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, nor that it needs to be democratic in any way. And besides, the details of how it would work are left to the Parliament, which would retain the “power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures.”

In the past I’ve written about the racialised nature of the Australian Constitution, as well as attempts by the official “Recognition” process to find a way to remove its offending sections and replace them with pro-Indigenous and/or anti-racial-discrimination powers.[2] Contrary to popular mythology, the 1967 referendum didn’t deliver equal rights for Aboriginal people, but instead brought them under the race power, from which they had been excluded. This allowed the Commonwealth to make legislation about them as a racial group, whether this took the form of “positive” discrimination (granting land rights or native title, protecting cultural rights, implementing Aboriginal-only health and social programs, etc.) or “negative” discrimination (overriding cultural rights in favour of development in the Hindmarsh Island Bridge case, the Northern Territory Intervention, multiple suspensions of the Racial Discrimination Act, etc.).

Because significant post-1967 gains for Indigenous people had occurred under the aegis the race power, most Indigenous leaders — as well as supportive legal experts and politicians — were nervous that any attempt to remove racially discriminatory provisions needed to be balanced by creating a new constitutional power for Aboriginal advancement. This proposal ran aground after it provoked acrimonious splits on the conservative side of politics, with opposition to positive discrimination based on Aboriginality taking a similar form to more recent right-wing hostility to the Voice.

With the constitutional change process stalled, Aboriginal leaders were next infuriated by Prime Minister Tony Abbott ramming through major changes to the funding of Indigenous programs without bothering to go through the usual consultations, in May 2014. From this time on they warmed to the idea that they needed a permanent place within the state so as not to be shut out of influence over government decision-making again. In July 2015 a meeting between 39 leading activists, Tony Abbott, and then Opposition Leader Bill Shorten led to the drafting of the “Kirribilli Statement”, with one of the options canvassed being “a new advisory body established under the Constitution”.[3] This was based on an idea for a Voice first floated by Noel Pearson in his 2014 Quarterly Essay, “A Rightful Place”, although at that time Pearson still wanted the race power removed.[4]

While the 2017 “Uluru Statement from the Heart” is often portrayed as a plea to the Australian people from the grassroots of Indigenous communities, the Uluru Dialogues whose decisions it summarised were in fact official consultations carefully curated and tightly managed from above, as described by one of those who led them, constitutional law expert Megan Davis:

The dialogues were led by an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander subcommittee of the referendum council that I chaired. We sought advice from a sample of Nations and communities via a structured, deliberative process that walked representatives, chosen by local Indigenous community organisations, through a tightly structured, intensive civics program and an assessment of legal options for reform from the expert panel and the joint select parliamentary committee. Prior to the dialogues we spent a year in communities seeking permission, refining the process and running a trial dialogue. This was a very serious constitutional process. The question of meaningful recognition led to the Voice to Parliament being the primary reform across all dialogues. Agreement-making or treaty and truth-telling were non-constitutional but highly regarded as meaningful recognition. They were included in a framework of change known as Voice Makarrata.[5]

Little wonder that the Uluru Statement ended up with proposals so closely aligned with the direction that the most prominent Indigenous leaders had already been moving towards in the Kirribilli Statement. Most importantly, the Dialogues treated the need to remove or replace the race power as an issue of lesser importance.

Suffice to say, it shouldn’t be surprising that the Yes campaign has found it so hard to sell the Voice as a blow against racism when it rests on the continuation of the race power. Or to claim that a special permanent state body based on “Indigeneity” (which is in part defined by shared ancestry) is different to one based on racial distinctions (also usually defined by shared ancestry). Or to speak of how it will address Indigenous disadvantage when it doesn’t have to act in Indigenous interests. Or how it won’t override claims of “never ceded” black sovereignty while at the same time as being incorporated into the Constitution of the state, the sole sovereign lawmaker of the land.

Or to call the Voice “representative” or “an enhancement of democracy” when it has not been proposed to be either. Or to tell people there is “plenty of detail” (“just Google it!”) available about what it will look like, such as the Calma-Langton Report, but then not want to debate those details because Parliament might decide on a different model.

And that’s leaving aside the multitude of mixed messages made by various Voice advocates about its role in future policies, treaties, and reparation claims.

‘NO PLAN B’

The failure of the Voice referendum will have a major impact on how Indigenous and mainstream politics relate to each other, a secondary consequence of which is likely to be a significant shake-up of power relations within the small but influential Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander political class, as well as its relationship to the Indigenous people it purports to represent.

In this sense Noel Pearson has been truthful that “there is no Plan B” by the current crop of Aboriginal leaders if the Voice fails. His promise to leave politics if that happens reflects that this has been their last-gasp effort to secure a permanent place within governance at the national level. Or as he formulates it, “Without a constant voice in the ear of the government and the parliament of the day, the myriad of issues that need to be tackled won’t be in the consciousness of the decision makers and the people who are allocating funding from Canberra.”[6]

Ironically, the push for a Voice locked into the structure of the state has come just as Aboriginal representation in Federal Parliament has reached its highest ever level, a greater share of parliamentary seats than the proportion of Indigenous people within the Australian population. This has led to the spectacle of supporters of an Indigenous “Voice” (singular) having to downplay the breakthrough of 11 Indigenous “Voices” (plural) being able to speak and vote. They’ve also attacked those Indigenous voices — like Jacinta Nampijinpa Price’s on the right and Lidia Thorpe’s on the left — that have refused to toe the line and support the Voice.

Similarly, No campaigners like Nyunggai Warren Mundine have argued that a single national Voice would force a false homogeneity onto the diversity of Indigenous interests, including traditional owners who identify with specific first nations, or individuals who are not connected with existing Indigenous organisations.

Perhaps predictably, a survey by the reputable pollster Resolve found that support for the Voice among Indigenous voters was running at just 59 percent a week out from the referendum, much lower than the 80 percent that polls had been showing at the beginning of the year.[7]

With a failure to corral it behind one state body — constitutionally enshrined and thereby given inordinate political weight not just in relation to government but to Aboriginal people — the fragmented and often bitterly divided nature of Indigenous politics will now be more obviously out in the open.

Much like non-Indigenous politics already is.

A POLITICAL ECHO CHAMBER

Meanwhile, Anthony Albanese’s decision to run hard on the Voice will have consequences for intra-ALP and wider left politics. It is hard to imagine a more dramatic squandering of popular good will, weighed down by a poorly judged campaign that showed all the signs of having been hatched in a political echo chamber convinced of its own ability to drive social progress by telling voters to simply trust its good moral intentions.

That has been exacerbated by Labor’s decision to play hardball politics, seeking early on to wedge the Opposition by refusing to make concessions in delivering on a “polite, modest request” that had come directly from the Indigenous authors of the Uluru Statement from the Heart. After all, who would want to question the proposal unless they were racists or reactionaries? However, this guaranteed — after a brief period of disorientation on the right — that the Voice would be a partisan issue.

Maybe Albanese was still on a sugar high from the Coalition’s historic thrashing at the last federal election, in which it lost formerly rusted-on urban bourgeois voters and seats to Teal independents and Greens, but his tactic also destroyed any illusory moment of national political consensus. Perhaps Labor tacticians should’ve spent longer pondering the fact that they’d won majority government with a primary vote of just 32.6 percent; hardly a firm base for such hubristic politics, even if it was cheered on by their press gallery fans at the time.

Just as importantly, by advocating for a significant Constitutional change while purposely revealing a minimum of detail on how it would be implemented, the government set up a situation in which voters are being told to “trust politicians” in whom public trust has been on a downward trend for decades.

The long-run decline of social institutions on which politicians and parties had relied for authority also bedevilled the Yes campaign’s claims to be garnering civil society support for the Voice. While not as pronounced as distrust for Canberra politicians, public wariness regarding the media, large banks and corporations, trade unions, and even organised religions meant that admonitions from these bodies to vote Yes could easily become a poisoned chalice.[8] This came to a head with Qantas, which had gone all-in on the Voice, being exposed for its lousy treatment of its workers and gross profiteering during the pandemic as well as the possibility it had gotten special favours from government on keeping competitors out of Australian airspace.

The contrast with ordinary voters’ own lack of influence on government decision-making around issues affecting their lives could not have been starker in the middle of a cost-of-living crisis.

With detail not on offer, the Yes campaign has alternated between, on the one hand, claiming that the Voice is no more than a modest reform that bestows minimal additional rights on a small minority of the population and, on the other hand, claiming it will produce dramatic changes in how government deals with Aboriginal people that will lead to positive social, economic, health, and cultural benefits where in the past there have only been failures. This has resulted in the curious phenomenon of Labor politicians in government — including Albanese himself — unable to explain why they can’t simply listen to Aboriginal people and implement policies beneficial to them now, given they all say they want to, as if the lack of a Voice was the only thing holding them back.

Given the shambolic state of the No side, its lack of consistent and coherent messaging, and the federal Coalition continuing to be in disarray from last year’s election, it seems implausible to credit much of the collapse in support for the Voice — as some on the left have — to the No campaigners’ Svengali-like ability to deploy fake news, fear, and division. What’s more, polls show that there has been only a small narrowing between the major parties since the referendum bill was debated and passed in May, and that the Coalition is still tracking below its disastrous 2022 primary vote, not what one would expect if the centre right was on the political upswing.[9] Similarly, while Albanese’s approval has declined considerably since the election, Dutton’s has essentially remained flat or even declined a little.[10] And the most detailed polling done on people’s attitudes to the Voice, from the very pro-Voice RedBridge group, suggests that once the Voice started to wobble in the polls it was among traditional Labor voters, those who had stuck with the party even as its core support slowly evaporated over recent decades.[11]

In the meantime, much of the left beyond Labor has fallen in behind the push by Albanese and Indigenous leaders, unable to offer a position on Indigenous self-determination independent of the narrow framework set by mainstream political elites.

For the Greens this involved dropping their clearly stated pre-election policy of putting Treaty and Truth before any Voice, so that they lined up with the Yes campaign and with where most of their voters were leaning on the issue, resulting in their First Nations spokesperson Lidia Thorpe quitting the party.[12] Far left groups, meanwhile, have mostly run the somewhat circular line that while there is nothing in the Voice for Indigenous people, supporting it is nevertheless essential to fight the racist right, which would be emboldened by the failure of Yes now that a referendum has been called.[13]

A BITTER DIVIDE

This last position has also crept into mainstream discussion, as attacks on the No campaign have become more prominent than trying to positively explain how the Voice is meant to work or how it might produce better outcomes. The bitterness of prominent Yes campaigners — implying or openly stating that the No vote is driven by some combination of racism and misinformation — was perhaps best expressed by Marcia Langton:

Every time the No case raises one of their arguments, if you start pulling it apart, you get down to base racism. I’m sorry to say it, but that’s where it lands – or just sheer stupidity.

If you look at any reputable fact-checker, every one of them says the No case is substantially false, they are lying to you.[14]

Despite claims that such criticisms have only been directed at the leaders of the No side, they are in line with the dim view that many Voice advocates have of voters as easily taken in by such appeals. Indeed, for some Yes supporters this referendum is fast becoming Australia’s “Brexit moment”.[15] For Noel Pearson it goes even deeper:

“It’s time to talk about the morality of the choices facing us as Australians. One choice will bring us pride and hope and a belief in one another. And the other will, I think, turn us backwards and bring shame to the country.[16]

Given the significant voter disengagement with the politics of the Voice that has been noted by pollsters, the attempt to apply such narratives to a public unsure about the merits of a constitutional change and worried that it might exacerbate social divisions risks reproducing one element of the UK’s unhinging over Brexit, in which “enlightened” politically engaged people turned on their “backward” fellow voters.

Because cost of living pressures have been preoccupying voters more than the Voice, the outlines of the post-referendum narrative from the left will likely involve addressing economic concerns while bitterly remarking how narrow-minded and self-interested No voters were for foregrounding these. No voters are already being characterised similarly to Hillary Clinton’s infamous description of Trump voters as a basket of deplorables and desperates — on the one hand susceptible to reactionary impulses and on the other driven to vote No by their difficult economic circumstances.

The size of the No vote and the public’s relative detachment mean that the post-referendum polarisation is not likely to be as extreme as that which followed the Brexit and Trump shocks of 2016. However, Yes advocates’ pronunciations of moral failure and contempt for the public are not a formula that can heal more fundamental rifts between a self-absorbed political class and a wary, fractious electorate.

[1] https://www.theaustralian.com.au/commentary/racial-divide-has-always-been-part-of-our-constitution/news-story/2fd0411184d3305e68284f46f375e98a

[2] https://left-flank.org/2015/06/11/australias-racial-state-indigenous-recognition-the-left/

[3] https://www.referendumcouncil.org.au/sites/default/files/report_attachments/Appendix%20G%20-%20Kirribilli%20Statement.pdf

[4] https://www.quarterlyessay.com.au/essay/2014/09/a-rightful-place

[5] https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/comment/topic/2022/08/06/what-happens-next-the-voice

[6] https://www.3aw.com.au/there-is-no-plan-b-noel-pearsons-strong-message-for-the-no-side-in-the-voice/

[7] https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/indigenous-support-for-voice-falls-but-keeps-majority-20231010-p5eb19.html

[8] https://theconversation.com/5-charts-show-how-trust-in-australias-leaders-and-institutions-has-collapsed-183441

[9] https://www.pollbludger.net/fed2025/bludgertrack/

[10] https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/newspoll

[11] https://x.com/KosSamaras/status/1706214900199276696

[12] https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/feb/06/senator-lidia-thorpe-to-quit-australian-greens-party-independent-black-sovereignty-indigenous-voice-to-parliament

[13] https://redflag.org.au/article/why-left-should-vote-yes-referendum

[14] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-09-13/marcia-langton-clarifies-no-camp-racism-comments/102848644

[15] https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/comment/topic/2023/09/16/the-voice-our-brexit-moment

[16] https://www.news.com.au/national/politics/noel-pearson-says-a-no-result-will-bring-shame-to-australia/news-story/6cdc09d53fd79f2e69d58b4a2dbb3d26

Grest to see you back, Tad.

I think one reading is that Albo has taken the same approach to this as has he has taken everywhere else – the path of least resistance. He’s put it to the electorate in its raw state to appease his base and from now on he can just shrug his shoulders and say he tried when it comes to indigenous matters.

However, if you want to give him some credit, he might be using this to bury debate on “Same Job, Same Pay” Bill which is actually a worthwhile reform.

Great analysis as always Tad, and very sad news of Piping Shrike’s passing. Vale.